The Sculptor in ancient Egypt

On this page...

© Australian Museum

Stone sculptures created by ancient Egyptian craftsmen are some of the most impressive and informative remnants of the ancient world. Sculptors had an important role in ancient Egypt as they carved substitute bodies for the tomb, small funerary statuettes and tombstones.

High and low relief

Throughout Egypt’s long history, sculptors worked with two methods of relief carving: high and low. High reliefs were those carvings that stood out from the surrounding surface which had been cut away. Low reliefs were images that were cut or ‘sunk’ into the surface material. These relief carvings were considered eternal so this method was often used in temples, tombs, stelae (tombstones) and sarcophagi (stone coffin).

Shabtis: workers for the afterlife

An important role for sculptors was to carve shabtis, small funerary statuettes. The dead were granted a plot of land in the afterlife and were expected to maintain it, either by performing the labour themselves or getting their shabtis to work for them. Shabtis were inscribed with a spell that miraculously brought them to life, enabling the dead person to relax while the shabtis performed their physical duties.

Shabtis have a long history as funerary items for tombs. They first appear in the Middle Kingdom about 2100 BCE, replacing the servant statuettes that were common in tombs of the Old Kingdom. Individually sculpted, they were designed to represent the owner and only one or two were placed in a tomb. By about 1000 BCE shabtis became simplified in form, with the wealthy now having one for every day of the year and overseer shabtis to manage them. This was due mostly to an ideological shift – they now represented servants rather than the dead person. The last shabtis were used in the late Ptolemaic Period, as attitudes to death and the afterlife had changed.

Substitute bodies

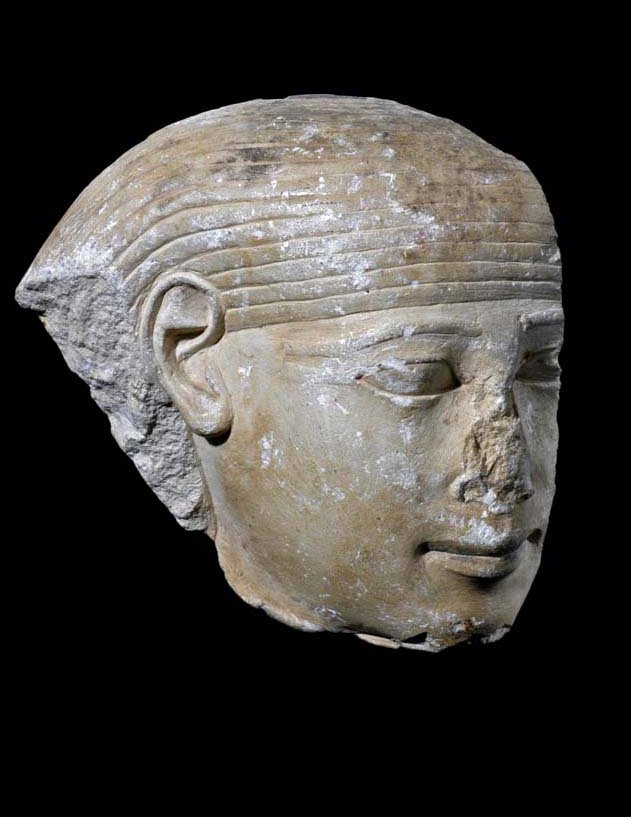

Sculptors made statues for inclusion in tombs because they were considered substitute bodies for the souls. This is why the tomb owner, in statue, was depicted as calm, young and strong – created without defect so the person’s spirit could maintain an ideal existence in the afterlife. These statues gave the person’s ka (or life force) a body to inhabit so it could move from the burial chamber to the mortuary chapel where it could consume offerings. Also, if something happened to the mummified body, a person’s ba or spirit could take up residence in these statues.

Stelae - ancient tombstones

The Egyptian expression for stelae, wd, generally means ‘monument of any kind’. They were most often used as grave markers that contained carvings and/or paintings of the tomb owner, often with his family, and inscriptions of prayers to various gods of the dead. They look remarkably like tombstones because tombstones are a modern manifestation of these kinds of markers symbolising the passage between the land of the living and the land of the dead. Sculptors made these types of stelae to function as substitute false doors as they share many physical characteristics such as shape, images and inscriptions.