Japanese Antarctica expedition and the Shirase sword

Australia, Japan and Antarctic exploration are linked through the history of this sword.

About the expedition

Australian geologist and Japanese explorer are the protagonists in a story about a legendary weapon known as the Shirase sword. The Japanese Antarctic exploration of 1910-12 under the command of Lieutenant Nobu Shirase was greatly aided, if not rescued from derailment, by Professor Edgeworth David – Antarctic explorer and accomplished geologist at the University of Sydney.

The sword timeline:

- 1648 – made by Mutsu no Kami Kaneyasu

- 1910 – presented to Lieutenant Shirase (1861-1946) by Tasaburo Fukuda

- 1911 – presented to Professor David (1858-1934) by Lieutenant Shirase

- 1934 – inherited by Mary David (1888-1987)

- 1979 – gifted to the Australian Museum by Mary David

The Shirase expedition story

In 1911, three expeditions set out to reach the South Pole. Amundsen and Scott succeeded and are internationally famous. The third group, a Japanese expedition led by Lieutenant Nobu Shirase, did not succeed, but Shirase and his men are celebrated heroes in their homeland.

Shirase's expedition reached Antarctica in the autumn of 1911. It was too late to make their attempt before the onset of winter, so the expedition sailed to Sydney to wait for spring. In Sydney the expedition set up camp in what is now Parsley Bay Reserve in Woollahra, where they lived for several months.

The Sydney press ran stories that suggested the Japanese party were on a spying mission, as it was camped near the South Head military establishment. These accusations created difficulties for Shirase's party, who needed to repair their ship and re-supply the expedition.

Tannatt Edgeworth David, professor of Geology at the University of Sydney and a Trustee of the Australian Museum, defended the Japanese party and assisted them in their negotiations with the local authorities and businesses. Edgeworth David had done fieldwork in Antarctica with Douglas Mawson and freely shared his knowledge and experiences with Shirase. The two men developed a close friendship. In November 1911, as the Japanese prepared to depart again for Antarctica, Shirase expressed his gratitude by presenting his own 17th century Japanese sword to Edgeworth David.

Shirase's second attempt to reach the South Pole was also unsuccessful, though his expedition explored a large area of new territory. The expedition received a heroes' welcome on their return to Japan, and the western end of the Ross Ice Shelf in Antarctica today bears the name Shirase Coast in honour of the attempt.

In 1979, Mary Edgeworth David, the professor's daughter, presented the sword to the Australian Museum after it had been restored in Japan. The sword is an excellent example of the work of Mutsu no Kami Kaneyasu, a master swordsmith who worked in the period 1600-1650.

The sword's powerful symbolism of friendship and goodwill has led hundreds of Japanese people to visit the Australian Museum specifically to see the sword. The sword has also travelled to Japan where thousands of people came to see it on display in the Shirase Antarctic Expedition Memorial Museum in Konoura, Shirase's birthplace, and at the Nagoya Maritime Museum.

A memorial plaque installed in 2002 at Parsley Bay Reserve commemorates Lieutenant Shirase's expedition.

Translation of the letter written to Professor Edgeworth David by Lieutenant Nobu Shirase, leader of the Japanese Antarctic expedition of 1911

Japanese Antarctic Exploration Ship, KAINAN MARU

Sydney, November 18th 1911

Professor T. W. Edgeworth David

University of Sydney

Dear Sir,

As you are aware, we are leaving Sydney tomorrow on our journey to Antarctica; but we cannot go without expressing our heart-felt thanks to you for your many kindnesses and courtesies to us during our enforced stay in this port.

When we first arrived in Sydney we were in a state of considerable disappointment, in consequence of the partial and temporary failure of our endeavour. To add to this we found ourselves, in some quarters, subjected to a degree of suspicion as to our bona fides, which was as unexpected as it was unworthy.

At this juncture you, dear sir, came forward, and, after satisfying yourself by independent inquiry and investigation of the true nature of our enterprise -- which no one in the world at the present day is better able to do -- you were good enough to set the seal of your magnificent reputation upon our bona fides, and to treat us as brothers in the realm of science.

That we did not accept all of your kind offers to bring us into public notice was not from any lack of appreciation of the honour you desired to do us. But we felt there was a danger that your generosity and magnanimity might unwittingly place us in a position to which we could only regard ourselves as entitled when our efforts should have been crowned with success.

Whatever may be the fate of our enterprise, we shall never forget you.

We are, Dear Sir,

Yours most sincerely,

Nobu Shirase, Commander

Naokichi Nomura, Captain of Kainan Maru

Terutaro Takeda, Scientist

Masakichi Ikeda, Scientist

Seizo Miisho, Physician

Shirase Sword E76356 Photographer: Carl Bento

Image: Carl Bento© Australian Museum

The Samurai sword katana is not an ordinary weapon. It has an important place in Japan’s military past and cultural history, where its appreciation is carefully measured. The swordsmiths are included in lists with special rankings. In one such list, compiled by Tomita Kiyama in 1933, the grading system is borrowed from ranking Sumo wrestlers.

In this classification several senior, established swordsmiths are given special honorary rankings, while the remaining craftsmen are ranked within two parallel groups – one more prestigious than the other. An Osaka swordsmith - Mutsu no Kami Kaneyasu - is placed in a special honorary position with a handful others who stand out in their accomplishment above the hundreds of their peer swordsmiths.

We don’t know much about Mutsu no Kami Kaneyasu. He was from the provincial town Yamato in Kanagawa Prefecture - central Japan, west of Yokohama - and an apprentice of the highly respected and influential Tegai School of sword-making. In about 1644 he came to Osaka– then an prominent cultural and economic centre.

This was an important period (Sho-ho era) in katana-sword history. Katana was then fully developed, distinctly different from the longer and older type of samurai sword tachi and, importantly it was no longer a less costly, shorter sword of lower ranking warriors, but a superior weapon much valued by the cream of samurai warriors. It was possible to draw the katana and strike in one rapid movement and it is likely that this functional advantage made it the weapon of choice.

Along with the demand, the swordsmiths set to work, refining its quality and functional properties in various sword-making schools of this period.

This sword is an excellent example of the craftsmanship of Mutsu no Kaneyasu, a master swordsmith who worked in the period 1600-1650. He produced this sword in Osaka (Settsu no Kuni) in 1644-48. We know this because the swordsmiths of that time often signed their work, inscribing their name on the tang – a base where the handle is attached. Mutsu no Kami Kaneyasu had a peculiar habit of engraving his swords with a mirror image signature where the characters were inscribed backwards.

This sword was presented to Lieutenant Nobu Shirase by his sponsor Tasaburo Fukuda in 1910, just before Shirase embarked on his voyage of exploration to Antarctica. Shirase later gave the sword to Professor Tannatt Edgeworth David as a gift in gratitude for his assistance to the Japanese Antarctic Expedition in Sydney in 1911.

In 1911 there were less than twenty houses in Parsley Bay, as the land had only recently been subdivided from the Wentworth estate.

The earliest residents were ship pilots and sea captains, council aldermen, and other professionals. For years the reserve itself had been a Sunday picnic ground and a favourite swimming and recreation area for Sydneysiders, with fisherman “individualists” camped in rock shelters nearby.

In the scrub on the western side of the small reserve the Japanese erected their prefabricated timber hut, originally intended for Antarctica, and three tents for equipment, food and bathing. Some of the crew stayed on board the Kainan-maru while it underwent repairs in Jubilee Dock Balmain, and Captain Nomura returned to Japan to acquire more sledge dogs and petition for extra funding.

Expedition members described the camp:

“This is where we live… surrounded by dense overgrown old trees… guava, bottlebrush, evergreen oak and pine. They give shelter from the breeze and make this a very peaceful spot. Standing on the rising ground behind the encampment you can gaze up at the hillside or turn to look at the sea below. Far across the water North Harbour, Manly and a number of other places are just visible through the mist and clouds. It is like a landscape painting come alive”. [Expedition Record, p.86]

The local residents had no warning of the expedition’s arrival, but friendships were soon established:

“As time went by and we continued to live in our temporary home, the local people came to understand our true intentions and gave us a great deal of support. They visited us from time to time, bringing all kinds of gifts. There were constant comings and goings between us and our nearest neighbours, who were especially kind, and on Saturday and Sunday afternoons there were always so many visitors that we were very busy receiving them.” [Expedition Record, p.88]

The newspapers reported on activities at the camp, and the local residents’ reactions. In June 1911 the coronation of King George was celebrated by the expedition members, who decorated the campsite with British and Japanese flags, demonstrated martial arts and provided refreshments for a combined audience of locals and members of the Japan Association. [SMH 23 June 1911]

As the expedition was gearing up for the second voyage to Antarctica in October 1911 a Herald reporter commented:

“During their wintering in Parsley Bay the Japanese proved themselves estimable neighbours, their camp was always a model of cleanliness, and the people of the district extended to them friendship which was fully reciprocated.”[SMH 10 November 1911]

On 19 November 1911 the Kainan-maru set sail again for Antarctica. As it proceeded out of the harbour it made a brief stop back in Parsley Bay “to enable us to bid a final farewell to the local people”. The Japanese delighted to find the throng on the wharf “Cheering and waving their white handkerchiefs and black hats in the air’ [Expedition Record, p.94]

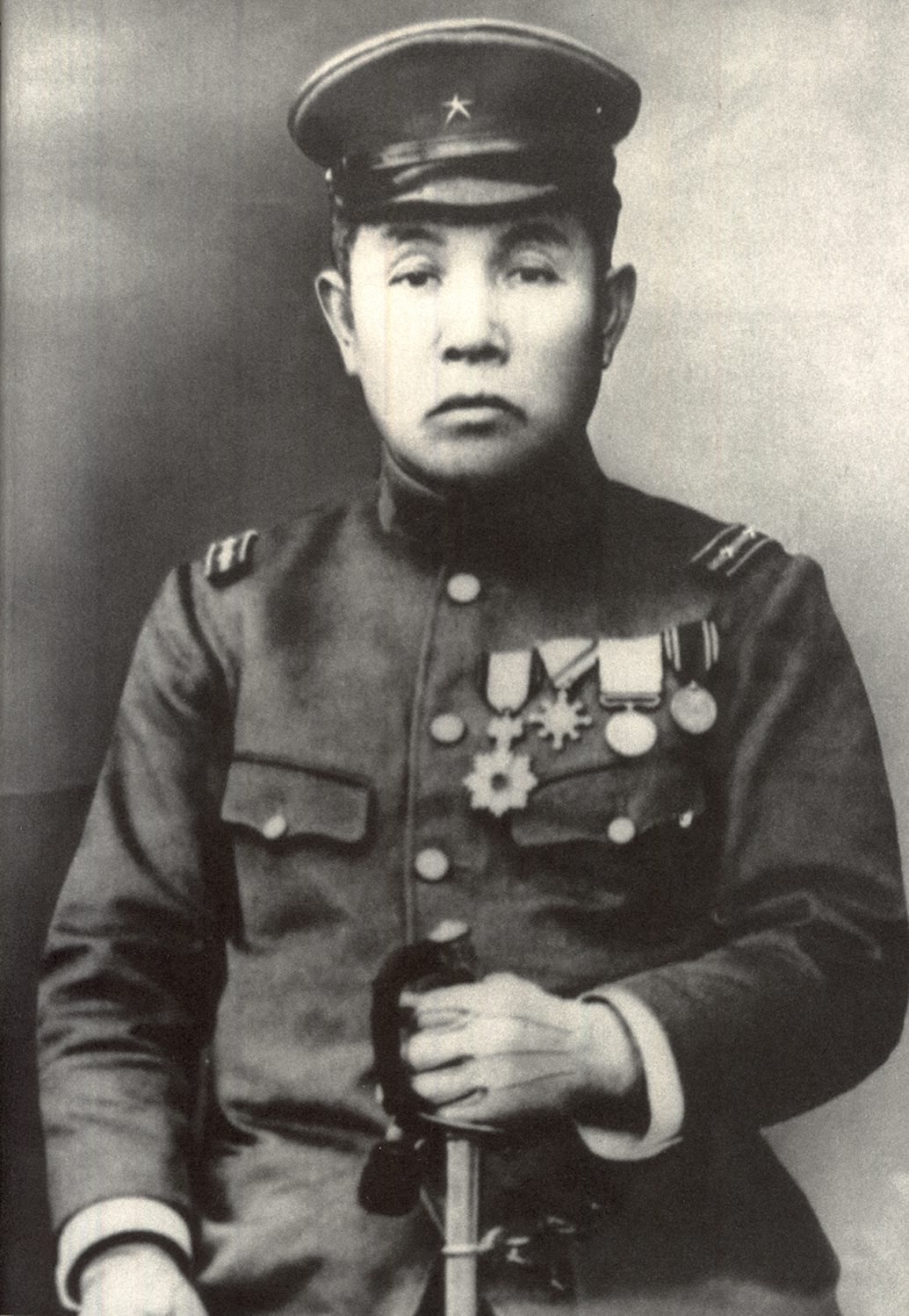

Lieutenant Nobu Shirase: Portrait

Image: Unknown© Australian Museum

Nobu Shirase (1861-1946) was a man of outstanding qualities and passion. As a boy he developed an enduring interest in polar exploration. Military conflicts punctuated his life and hampered his dreams.

He was seven when Japan was convulsed by the civil Boshin War of 1868-69. The conflict was partially triggered by foreign interference in Japanese affairs, but in the end it accelerated the process of modernisation.

The photo below from this period illustrates these trends, where the old-style samurai mingled with warriors in military uniforms. If born earlier Shirase could have become a samurai, but instead he went to military school and at the age of 20 joined the Army.

Satsuma clan during Boshin War of 1868-69 in Japan by Felice Beato

Image: Felice Beato© Australian Museum

In 1893-94 Shirase spent a year in the Alaskan Arctic on a covert military assignment. He experienced extreme deprivation and hardship in the polar winter which decimated his crew – Shirase was one of two surviving officers. The first Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95 was not an ideal time for exploration, nor was the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05.

Shirase must have had ambitious ideas, possibly to march to the North Pole. When two Americans - Frederick Cook and Robert Peary - claimed they reached the North Pole in 1908 and 1909, Shirase turned his eye to the South Pole. It was hard to raise enough money or to find sponsors in the post-war period. However, he received small donations from individual people whom he described as from the ‘student class’.

In November 1910 the Shirase expedition of 27 men and 30 dogs was ready to depart to the Antarctic. By then the Norwegian expedition led by Roald Amundsen and the British expedition by Robert Falcon Scott were on the way. They both reached the South Pole just one month apart, in December 1911 and January 1912 respectively. Meanwhile Shirase attempted to land on the Antarctic in March 1911, but it was too late in the season and the party sought shelter, additional provisions and money in Sydney where they arrived in May.

Unfriendly reception and suspicion of espionage made Shirase’s seven months camping at Sydney Harbour a highly distressing experience. It’s possible that the helping hand and friendly support offered by Professor Tennatt David propped up Shirase’s resolve and made the 1912 exploration of the Antarctic possible. David, a celebrated geologist and polar explorer, only three years earlier took part in the Mawson expedition to locate the South Magnetic Pole. On his departure from Sydney, Shirase gave David his highly treasured samurai sword as a gesture of respect, gratitude and friendship.

The Shirase party explored the Ross Ice Shelf some 160 miles ‘inland,’ as well as the coastal areas of King Edward VII Land. He returned to Tokyo in 1912 as a hero. But he dedicated many years to repay the enormous debt for the expedition and to document and publish the records of the explorations. He witnessed the turbulent times of Japanese military expansion during the World War I and the tragedy of the Second Sino-Japanese War of 1937-45 (World War II). These tumultuous times were not favourable for explorations which required peace and international cooperation.

During the last years, nearly forgotten, Shirase lived in a modest rented room above a fish shop where he died in 1946.

Explanation:

Samurai were the warriors or military nobility in pre-industrial Japan. The term can be found in the 10th century Japanese poetry.

Reference:

Chet Ross. 2010. Lieutenant Nobu Shirase and the Japanese Antarctic Expedition of 1910-1912: A Bibliography. Published Adelie Books, Santa Monica

Professor Edgeworth David: Portrait

Image: AM Archives© Australian Museum

David was Professor of Geology at Sydney University, Trustee of the Australian Museum, a member of Shackleton’s Antarctic expedition of 1907-9, and a respected Sydney scientist. Residents of Ashfield, the Davids had been guests at garden parties given by the Japanese Consulate in nearby Croydon, so would have been familiar with Japanese culture and affairs.

As soon as he heard of the Shirase Expedition’s arrival Professor David publicly praised their brave achievements under such adverse conditions, and invited Shirase to come and speak with him about the scientific plans for their next voyage. Responding to reports suspicious of the expedition’s motives he commented,” To raise an outcry against them on the purely imaginary grounds that they are spies is worse than inhospitable, it is sheer nervous stupidity.” [Daily Telegraph 3 May 1911]

In a lecture given in the Town Hall in June 1911 to raise funds for Mawson’s upcoming Antarctic expedition, David commended the Japanese, who he was honoured to have as guests that evening.

“I can assure you that of all the expeditions that have gone out to Antarctica there has been no more genuine expedition than that of which I am now speaking. It has been sent out by our brave allies, the Japanese.” [SMH 1 July 1911]

David also helped with the practical matters of equipping and stocking the ship, as he understood being a veteran himself the requirements of such an expedition. Lieutenant Shirase later said, “it was extremely fortunate for us that David… was living in Sydney”, and noted that chief scientist Dr Takeda and others benefitted greatly from listening to David’s Antarctic experiences. On 19 November 1911 Professor Edgeworth David and Douglas Mawson came on board the Kainan-maru with other friends and supporters to farewell Nobu Shirase and his team as they made their way out of Sydney Harbour to begin the second Antarctic voyage. It was on this occasion that Shirase presented Professor David with the Japanese sword and letter of thanks for his assistance to the expedition during its stay.

On their return to Sydney in 1912 Dr Takeda talked of handing over the results of the expedition to Professor David -meteorological, astronomical, and geographical data. The second Shirase Antarctic Expedition had sailed further south than any other, and established that King Edward VII land was in fact an island as David had predicted.

For a detailed account of the expedition, see The Japanese South Polar expedition 1910-12. A Record of Antarctica. Compiled and Edited by Shirase Antarctic Expedition Supporter’s Association. Translated into English by Lara Dagnell and Hilary Shibata, The Erskine Press and Bluntisham Books 2011

Some suggestions for exploring this story further.

The Japanese South Polar expedition 1910-12. A Record of Antarctica. Compiled and Edited by Shirase Antarctic Expedition Supporter’s Association (Nankyoku Tanken Koenkai). Translated into English by Lara Dagnell and Hilary Shibata, The Erskine Press Norwich and Bluntisham Books Huntingdon 2011

Shirase Antarctic Exploration Memorial Museum: Shirase Nankyoku Tankentai Kinenkan. Akita, Japan . Shirase Nankyoku Tankentai Kinenkan, 1991

D. F. Branagan and T. G. Vallance, David, Sir Tannatt William Edgeworth (1858–1934), Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/david-sir-tannatt-william-edgeworth

D.F.Branagan, T.W. Edgeworth David: A life: geologist, adventurer, soldier and “Knight in the old brown hat”; Canberra, National Library of Australia 2005

Britten, Jane and Yeh, Caroline, Parsley Bay: place of the heart. Woollahra, Woollahra Library. 2000

Pain, Stephanie, The rice man cometh.(adventurous story of Nobu Shirase, a Japanese explorer), New Scientist, v.212, no.2844-2845, 2011 Dec 24, p.54(4)

Ross, Chet, Lieutenant Nobu Shirase and the Japanese Antarctic Expedition of 1910-1912 : a bibliography. Santa Monica, CA : Adelie Books, 2010.

TROVE (National Library of Australia) online lists

- “Japanese Expedition” Created by Robbosun, trove.nla.gov.au/list?id=16126

- “Scott Expedition” Created by Robbosun, trove.nla.gov.au/list?id=15529

- “Amundsen” Created by Robbosun, trove.nla.gov.au/list?id=16343

- “Japanese in Sydney 1900-1910” Created by Bluejay, trove.nla.gov.au/list?id=41884