Conserving koalas: using DNA to look at the big picture

Looking at koala DNA from across the country gives us insights into their past, to help conserve them for the future.

Koala genome team at work at the lab, Australian Centre for Wildlife Genomics at the Australian Museum Research Institute.

Image: Stuart Humphreys© Australian Museum

The koala is a unique and internationally recognised Australian icon but its conservation and management is complicated. Although most management of koalas currently occurs locally, our genetic study has revealed the big picture of a more complex and dynamic evolutionary history that needs to be considered in future management.

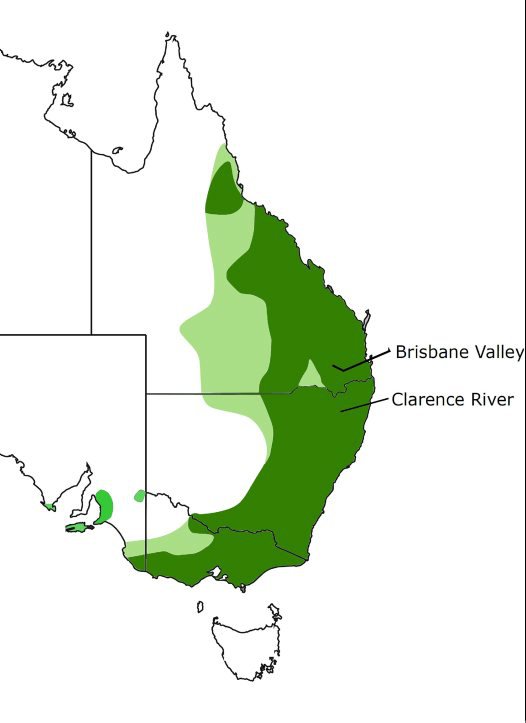

Koalas are found throughout eastern Australia from north Queensland down to Victoria and South Australia. In the northern parts of their range koala populations are declining, largely due to habitat loss and fragmentation, while populations in the south are overabundant, sometimes requiring management to control numbers. Because of these contrasting population trends, koala management tend to be focussed at local scales such as local government areas. While local management is important it often occurs without much reference to the bigger picture. To further complicate management, koalas also show variation in morphology, or appearance, across their distribution, which has led some researchers to split the species into three sub-species.

DNA can provide important additional information to inform conservation and management, but most previous genetic studies of koalas have focused on local areas rather than the whole range of the species. Because of differences in methods used in these different studies, comparing their results to gain a big picture is difficult.

© Neaves et al. (2016)

Our study analysed the largest and most widely distributed sample of koalas gathered to date and confirmed that koalas represent a single species, with no evidence to support separation into subspecies.

Although a single species, our analysis of geographic and genetic data revealed historical splits between populations – that do not reflect subspecies previously recognised by some studies – and we can now see that, like many other Australian mammals, koala populations were separated by two known biogeographic barriers (Brisbane River Valley and Clarence River Valley) during the last ice age about 20,000 years ago, when forest habitat in Australia became more restricted and fragmented. However, since the end of the dry period associated with the ice age the impact of these barriers has been removed and they no longer restrict the movement of koalas.

© Australian Museum

Early management of koalas in South Australia and Victoria involved extensive reintroduction and movement, or translocation, of koalas among populations, and this was apparent in the genetic patterns we observed. In many areas in these States, koalas have very low levels of genetic diversity compared to northern populations. The majority of these populations appear to originate from the same area as predicted from historical records. In contrast, koalas in north-eastern NSW and south-east Queensland have high levels of unique diversity.